"We define that the holy icons, whether in color, mosaic, or some other material, should be exhibited in the holy churches of God, on the sacred vessels and liturgical vestments, on the walls, furnishings, and in houses and along the roads, namely the icons of our Lord God and Savior Jesus Christ, that of our Lady the Theotokos, those of the venerable angels and those of all saintly people. Whenever these representations are contemplated, they will cause those who look at them to commemorate and love their prototype. We define also that they should be kissed and that they are an object of veneration and honor (timitiki proskynisis), but not of real worship (latreia), which is reserved for Him Who is the subject of our faith and is proper for the divine nature, ... which is in effect transmitted to the prototype; he who venerates the icon, venerated in it the reality for which it stands."The Seventh Ecumenical Council, Nicea (787) Sandro Botticelli, "Madonna of the Magnificat" (c.1483)

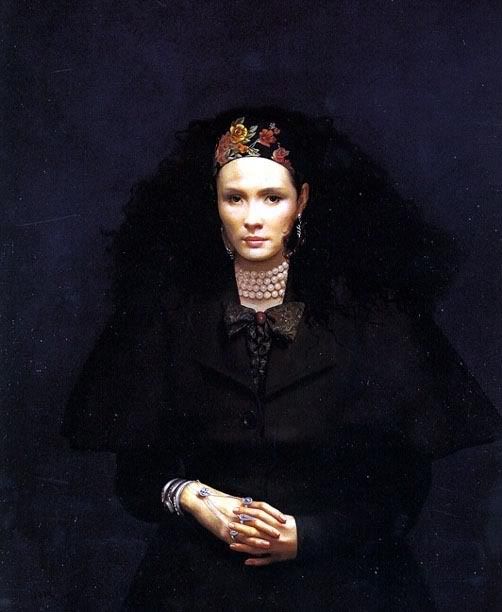

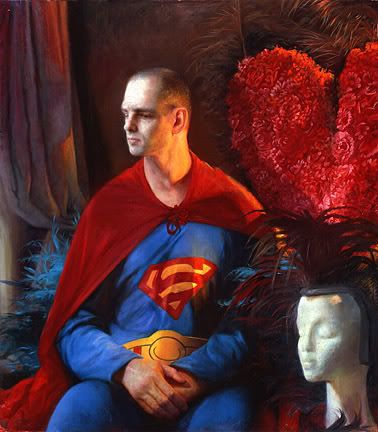

Sandro Botticelli, "Madonna of the Magnificat" (c.1483)Let us take two portrayals of the Virgin Mary.

For the first let us use Botticelli's "Madonna of the Magnificat" as an example. We choose it not because it is somehow exceptional – it is that, widely admired at the time of its composition, it remains an impressive display of skill and composition – but because the themes by which the Virgin is portrayed are in many ways quite typical. It is not known who commissioned the piece, but whoever it may have been, they were extremely wealthy. To begin with, the panel is extremely large, and each of the characters is nearly life-sized. Given the expense of gold paint, artists were generally very sparing in its use. But here Botticelli uses it in extravagant fashion. Mary's robe and dress are very intricately embroidered in gold. The crown that is being lowered upon her head is likewise of a very delicate gold design. The halos are of course of gold paint, and there is gold embroidery on some the minor characters as well. Perhaps most amazingly, Botticelli even used gold paint to supplement and achieve the overall hair color that he desired the Virgin to have.

Likewise, Mary bears the marks of royalty. She is being crowned Queen of Heaven as she writes, by two angels (she is penning the Magnificat found in the gospel of Luke). There are a number of stars in the crown adapting one typical portrayal of the Queen of Heaven with stars at her feet in a manner more appropriate to the tondo. Her clothes are likewise rich and lush. The royal blue is almost a mandatory Marian color, as is the deep red dress underneath. The angels gather round her as attendants, two of them holding the book open for her as she writes, their own clothing testimony to the wealth of the one on whom they wait.

Now while it is true that these traits lead us to an appreciation of the wealth of the commissioner, to think that this is the only function would be not merely cynical, but to fundamentally misunderstand the message of the painting. Botticelli's Christendom is a great chain of being that stretches from the lowliest depths of creation up to the heights of the divine. In order to analogously express this the artist takes those things which are most beautiful, those things which signify power, royal authority and grace to humanity here below, and uses them to express to the benevolent rule of the Queen of Heaven (in this case). Thus, it is not only the picture itself which, in iconic fashion, directs the viewer beyond themselves toward a greater understanding of Mary, but in fact the viewer is likewise directed towards the aristocratic family who commissioned the painting; they are understood by all to analogously portray the divine through the beauty of their lives and the benevolence of their rule. Thus the magnificent expenditure is not merely a decadent display, but a recognition that their wealth is at the service of something that transcends them. The image of royal power rebounds back upon the commissioner to measure and judge them – are they a dim but adequate reflection of the power of God in their use of earthly power?

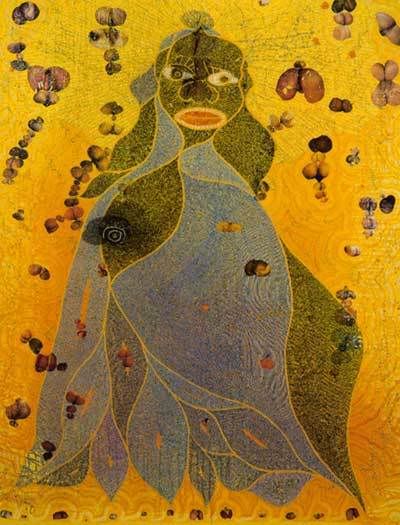

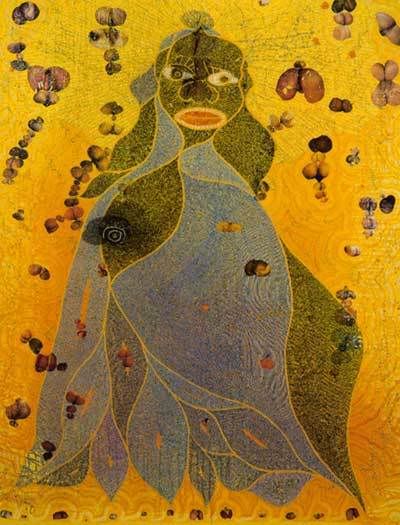

Chris Ofili, "The Holy Virgin Mary" (1996)

Chris Ofili, "The Holy Virgin Mary" (1996)For our second example, let us examine Chris Ofili's controversial "Holy Virgin Mary".

Here the composition is extremely simple. Mary, who has seemingly African features (Ofili is himself a Roman Catholic of African origin), looks out at the viewer. She is not Botticelli's aristocrat. There is no finery here. Simple earthy tones are used. The painter used both paint and elephant feces to achieve the effect he wanted with Mary. The beings that seem to flutter around her like butterflies, what one would traditionally identify as cherubs, turn out to be the buttocks and genitalia of various black women, cut from pornographic magazines and various blaxploitation films.

Obviously Ofili is addressing his audience in a much different way than Botticelli. He does nothing to invoke wealth and power. Mary is very common. But assuming that Ofili's purpose was not simply to piss off Mayor Guiliani, what purpose does the inclusion of scatological and pornographic elements serve. Why portray something he calls holy by means of so-much-shit?

The fact is that we no longer live in Botticelli's world. While gold may still indicate power, the sources of power are no longer considered as benevolent as they were. They are no longer, even in theory, interested in the human good, nor the common good. The powers represented by gold, by big blue, are the market, governments and corporations: the instruments of capitalism. These are things that exert their control over the audience, penetrate every sector of their lives, and allow no escape. Capitalism remains, at best, neutral with respect to the human good, and judges things only as commodities, reducing everything that falls within its grasp (which is nothing less than everything). Thus Ofili turns to waste, literally to shit. His voice is speaks according to that which is not valued by capitalism - whether it is to feces or to those parts of humanity which society views as so-much-shit - because that is what capitalism does not value; it is that which at least has a chance of escaping capitalism's control. Shit becomes the way of negating the demonic influence of the culture industry which embraces every part of human life and denies humanity any escape. Only shit, in the closed world of capitalism, might represent something beyond capital, can represent the holy, because shit is what is given off and left behind after the consumer consumes.

Yet one is left to wonder if Ofili can accomplish his purpose. Does not this negation of the values of capitalism not really just affirm them by turning them on their head. The use of shit only has meaning because of the value-system it is negating. Thus the painting itself is tied to, and is worthless without, capitalism. It needs capitalism to have value and to mean anything. Has Ofili done anything more than show capitalism a way of valuing that which it had previously excreted as worthless, further increasing its range of influence and control? Is this not what

Dalí foretold when he exposed Liberal-Capitalist society's unconscious in bluntly scatological terms. Ironically Ofili's painting ended up in the hands of a wealthy collector before it was lost in a fire. Ofili's problem is not unique; the problem is, how does one speak of the Beyond, of the divine, given that our language is always earth bound? Is it possible, or is capitalism's closure of life within its all encompassing web the truth of who we are?

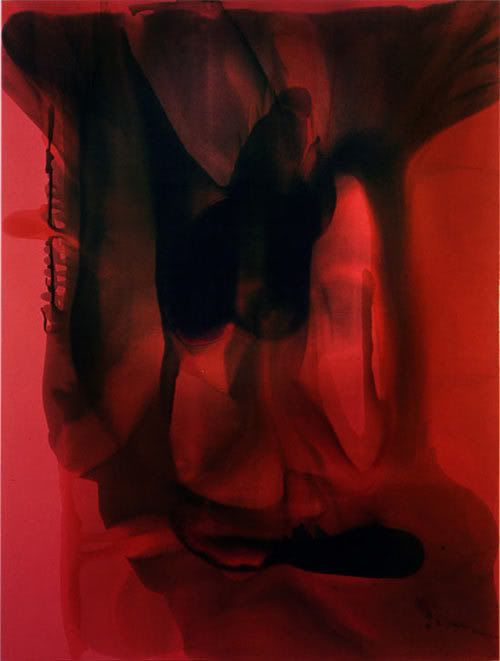

Mark Rothko, Untitled (1968) [Acrylic on Paper]

Mark Rothko, Untitled (1968) [Acrylic on Paper]Perhaps the best way to think of the relation between Botticelli and Ofili is in these linguistic terms. They are both attempts to speak about that which is holy. In the theological tradition there is a distinction made between positive speech about the holy (cataphatic language) and negative speech (apophatic language). Botticelli is clearly cataphatic language. Living in the middle of a Christendom which, according to its own self-understanding, attempts to direct the human person towards the divine, Botticelli not surprisingly uses those things that his culture values in order to express that impulse toward the holy. Ofili on the other hand resorts to an apophatic language, denying that the things which we value are holy at all. This is again, not surprising, since the culture in which Ofili speaks no longer sees a connection between its actions and the religious, which is granted a private and interior existence if it is affirmed at all.

But it is important to note, in order that BOTH forms of language not fall into idolatry, that the two forms must (and do) work together. It is not simply that every Botticelli needs Ofili's corrective (and vice versa), but that both elements are at work in both painters. The cataphatic and apophatic are correlates of one another which together attempt to open language onto a horizon which transcends it.

One should not be naive and think that Botticelli actually believes that his positive portrayal of the Virgin Mary in some way represents a realistic representation of her. He is well aware she is not a European noblewoman, nor was she someone who lived her life in wealth (nor let us be naive and think that Botticelli is not privileging a European, noble, Mary for the same reasons that he uses golds and blues). There is a negation, a falseness, that is built into the language itself that allows the viewer to see through, to see beyond what is merely said. In so doing, Botticelli not merely affirms but negates that which he speaks. As already mentioned, the commissioners, no less than the painting itself, can be at best, dim images of the holy towards which their eyes are turned.

Likewise, Ofili's negations cannot function without something to negate, something of value, something that is good: even if one realizes, in the negation that the things we value as good are nothing but shit, fallen and broken.

Trapped as we are within the prison-house of language, that language must be taken beyond its limits in order to express something beyond the prison. If there is to be hope for the future, we must crucify language, ignore Wittgenstein, and stake a claim on the Impossible – speak the unspeakable. This conjunction of the cataphatic and apophatic reminds us that we are not-yet what we desire to be, even though we do not yet know what it is that we desire. It reminds us not to settle for idols, but also to hold fast to hope.

-LoA