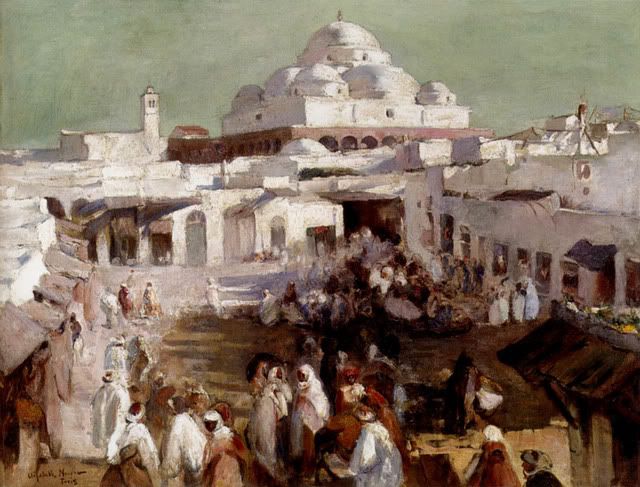

Elizabeth Nourse, "The Mosque, Tunis" (1897)

It is widely observed that Elizabeth Nourse's portrayal of women in real social settings marked a break with her contemporaries, especially men such as, her mentor, Jules Joseph Lefebvre. In Lefebvre aestheticism combined with the male gaze to produce abstract portraits of mostly nude women, absent any setting, without meaning, emptied of their content and of their very person. This allowed the female form to be taken in solely as an object of pleasure. Nourse's women, on the other hand, usually existed in household scenes, often with their children, in a manner that resisted the easy reification of the female body for the male viewer because they were embedded within social narratives that affirmed their vitality and humanity.

Jules Joseph Lefebvre, "Girl with a Mandolin" (late 19th c.)

I would like to suggest that we should read Nourse's "The Mosque, Tunis" in a similar fashion, once again against the tendency of the Orientalist tradition of most of her colleagues. If one takes her near contemporary Gerôme as an example one quickly sees the extremely dis-integrated vision of Arabia that he possesses. Apart from his fantasies of the Oriental harems and a few pictures of prostitutes, Gerôme's Arabia is nearly absent of women, revealing the extent to which the Orient was a playground for the European male's imagination of exotic and rampant sexuality. There are likewise portraits of isolated men: guards, merchants, traders, soldiers, or rulers. And finally there are a set of paintings that focus on Islamic prayer. These are particularly noteworthy relative to our theme as one compares Gerôme's vision to that of Nourse. Gerôme's pictures are either tightly framed or enclosed within the interior of the mosque which provides a backdrop to emphasize the alien nature of the event to the European viewer. He fails to make any connection between these religious acts and any other aspect of the society which he is "realistically" portraying, just as he fails to integrate the persons, both male and female, into their society. These are isolated objects, commodified persons and events packaged for easy consumption and playing to the tastes and expectations of the viewer.

Jean-Léon Gerôme, "The Call to Prayer" (1866)

Nourse's painting operates at a much different and more ambitious level than any thing Gerôme dared attempt. She encompasses a much fuller breadth of Islamic society within one vision and likewise understands the direction or goal that provides the interior dynamic to social life. A large group of people are portrayed going about a variety of tasks, men and women, spread throughout the square, walking to different parts of the city, as the larger city looms behind the market. Over it all, the mosque draws one's focus from the market higher toward that which stands at the center and pinnacle of the social and political life of its inhabitants and defines the rhythms of their day.

Mark Rothko, Untitled (1953)

-LoA

Elizabeth Nourse, "The Sewing Lesson" (1895)

8 comments:

Actually, I like both their styles, perhaps because I see more in their subject matter than they do.

i do think gerome is very talented. he is technically very gifted. but if you look at the body of his work he is never able to come to a whole picture of the arabia he is trying to portray. he is never able to pull it all together in the way that nourse does in this picture.

poor gerome. i regularly use him as a whipping boy, but i only do it because his stuff is so beautiful. beauty without vision...

My knowledge about art is very limited. Usually I depend on how the painting or sculpture makes me feel, but I can't hold in-depth discussions about styles and things like that.

I just wanted to say that I really enjoyed reading these different views and it made me take notice of things like image portrayal that I never really thought of before.

i am glad you are enjoying them. thats really all it takes to make me happy: to know someone is enjoying the images and possibly getting a little something out of what i write. i hope you will continue to visit. best wishes.

this post is really tight. im just going to shut up with that b/c deep down im a closet art critic and should have majored in art history.

you've definitely brought forth a couple of images i hadn't seen before.

you should definitely feel free to chime in. art is not exactly my speciality either. i missed my vocation in art history as well. thanks for stopping by and best wishes.

I enjoy your essays but I found your critique of Gernome unconvincing and hypercritical. You practically they label him as a sexist when in two portraits there are no women. I think people tend to see what want to see. Many orientalists escaped the west because they wanted a climate of more moral ease. And they saw what they wanted. Kinda like now

i tend to think the claim that gerome is sexist is pretty trivial. by our standards most of the painters would be sexist. i think the more amazing fact would be if gerome was not a sexist by out standards...for that matter it would be amazing if you failed to find examples of nourse being a sexist by our standards. that really is not the issue i take with gerome. the issue i take with gerome is the way in which the orient becomes a place where he projects desire. it is in danger of being a fantasy world.

once again, and i have tried to say this before. i only pick on gerome because i think he is important and good. he is worthy of recognition and interesting to critique. he breaks ground with his subjects and his topics. he presents a new world to europe. but gerome's experience of that world remains very fragmented and fantastic in ways he does not account for.

nourse and weeks on the other hand at least try to correct that. weeks by means of a kind of modesty: he remains very distant from his topics; exterior. nourse does it by actually trying to pull together arabia and not leave it fragmented mess in the way gerome does. and neither eroticizes islamic society to the extent that gerome does.

i am glad you enjoyed the essays and i very much appreciate you stopping by and taking the time to comment.

best wishes,

LoA.

Post a Comment