When one pays close attention to Jesus, as presented in Luke, one finds an interest and emphasis on the issue of poverty. Luke is well aware that in the everyday of functions of life, privilege and deference are usually extended to those with money, while those who are outcasts and those who are poor are ignored, discriminated against and often despised. But there are many scenes from Luke's Gospel, many of them unique to Luke, which demonstrate his belief that the coming of the Kingdom of God reverses this ordering of existence, and that Jesus embodies this reordering.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, "The Annuciation" (1898)

The Birth Narrative

There are two important incidents relative to the theme of poverty in the opening chapters of Luke. Having begun with the birth of John the Baptist and the announcement of that miraculous birth to John's father, Zachariah, Luke moves on to the birth of Jesus. While in the Matthew's account of the birth of Jesus the focus is largely on Mary's prospective husband, Joseph, and his indecision concerning what to do about the pregnancy of his bride (especially since he is not the father), Luke focuses instead on Mary. The angel Gabriel, who had already appeared to Zachariah (1.19), now appears to Mary to announce the miraculous birth of her son, who will be conceived without sexual intercourse (1.34-35).

Mary replies in the form of a hymn that echoes the song of Hannah (I Sam. 2.1-10). Hannah had been barren, and having prayed to God to grant her this blessing, she was granted a child which she dedicated to the service of God in gratitude for his birth. Now Mary also has a child who will do the will of God. Mary declares that the child will be a demonstration of divine strength. The proud are to be humbled, the powerful are deposed from their thrones, and the rich are stripped of their goods. God will then promote the lowest to prominence and assure that the hungry are fed (1.52-53).

But there is another more interesting and telling contrast between Matthew and Luke. In Matthew's account of the birth of Jesus, it is the rich and powerful from far off places that come to visit Jesus and celebrate his birth. The magi travel a great distance, and are of such standing that they are allowed to visit the political ruler of the land. Upon finding Jesus they give him very expensive gifts (Mt 2.1-12). By contrast, Luke has angels come and announce the birth of Jesus to shepherds sitting in the dark with their flocks. They do not bring gifts. Instead of being the one who receives gifts, Jesus is the gift that has been given to them. These poor, those who have nothing, are the ones on whom God has looked with favor (2.8-20).

What one finds in these two examples is that Luke is already using the birth narrative to argue that God's power and strength are not comparable to the royalty and power of this world. God's power and strength favors those who are powerless and poor. It is not something that attracts the wealthy, but overturns their tyranny.

Jules Bastien-LePage, "The Beggar" (1880)

Sermon on the Plain (and the Sermon on the Mount)

One of the most famous parts of the message of Jesus, as it is found in Luke, is what is commonly known as the Sermon on the Plain. The sermon is memorable if for no other reason than the repetitive cadence with which it is delivered. Over and over Jesus tells us "Blessed are..." and then goes on to list the blessed, those on whom God has looked with favor. Luke likewise follows this up with a series of "Woe to...", listing those who stand in opposition to the coming Kingdom of God. Luke's list is straightforward. God has come to bring the Kingdom to those who are poor, those who are hungry, and those who suffer and are hated (6.20-23). The Kingdom though stands in judgment against the fat, rich and decadent rulers of this age, since they have profited and taken delight at the expense of others, and they will be overthrown (6.24-26).

This is a remarkable enough example of Luke's privileging of the poor and reversal of standard conceptions of power, but it becomes even more striking when one contrasts Luke's account with that of Matthew. First of all, there is the setting. Matthew literally places Jesus in a position of height, overlooking his audience, and so, in Matthew, this comparable event in the life of Jesus is called the Sermon on the Mount. Luke places Jesus in a flat place which de-emphasizes the authority and power which is the focus of Matthew's geographic setting. Then, when one turns to the content of Matthew's Sermon on the Mount one quickly notices that it altogether lacks the curses (or "Woes") found in Luke's depiction of Jesus' sermon. The denigration of earthly power that is central to Luke is not to be found in Matthew's account. But while that absence is important, the alternative wordings that Matthew chooses for the blessings clearly show the power of what Luke has chosen to emphasize. Matthew, in two spots where he clearly overlaps with Luke, the blessing of the poor and the blessing of the hungry, chooses to spiritualize that blessing. For Matthew those who are blessed are "poor in spirit" (Mt 5.3) and those who "hunger and thirst for righteousness" (Mt 5.6). In Luke there is no such relativization of the blessing. It is those who are poor and starving that God has come to deliver, and who will be the graced and chosen in the new Kingdom.

David Teniers the Younger, "The Rich Man Being Led to Hell" (c.1647)

The Problem of Wealth

While Matthew does, in a limited way, suggest that wealth is an impediment in another place (Mt 19.24, a passage shared with Luke (18.25) and Mark (10.25)), what we find lacking in Matthew that is constantly present in Luke is the placement of this idea of the overturning of the relations of wealth and poverty at the very center of the message of Jesus. What is clear is that wealth ties a person to a set of conditions that are positively detrimental to their salvation. This is seen in two stories that are unique to the Gospel of Luke.

First there is the story of the one who prospers. As he prospers he begins to be concerned with how to store and protect his increasingly abundant goods. He builds barns, and new buildings, and makes plans to enjoy the good life. But, says Luke, such a person, in the process of becoming wealthy has become poor and disgusting in the eyes of God. Wealth is not an insurance that can guarantee the soul, nor can it purchase eternal happiness. When one is dead, one's wealth is lost and so one person who spends their life building and caring for their goods is truly impoverished for they have nothing of real value (12.13-21). Indeed, they are dead already.

But what is clear, from the second story is that this is not simply a subjective problem, a problem of the soul. Wealth exists at the expense of those without, and by its very existence treats with distain the poor that God has chosen as God's own. Thus one finds in the story of Lazarus and the rich man that the poor and sick Lazarus lies in the streets without respite, while the Wealthy lives in sumptuous luxury. But the earthly appearances are deceiving, and it is ultimately the poor and meaningless Lazarus who finds himself in Paradise, while the powerful are condemned and suffer (16.19-31). As Abraham's words to the Wealthy makes clear, the fault against the Wealthy is not subjective, but the objective fact of his wealth which itself created his own damnation; he is guilty of nothing other than being the Wealthy. In each case, in the coming Kingdom of God, wealth and power are overturned in favor of the powerless, poor and hungry.

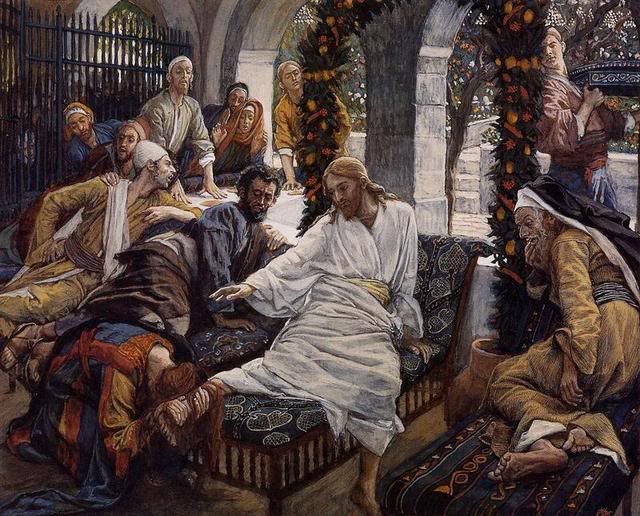

James Jacques Joseph Tissot, "Mary Magdalene's Box of Very Precious Ointment" (1902)

The Good Samaritan

In the end it is the outcast who knows and understands the sympathy, compassion and care that are the hallmarks of real divine power. Having suffered under oppression and having been despised, they are not offended by the suffering of others. And so, when, in the parable of the Good Samaritan, a man is waylaid, beaten, robbed and left for dead, the ones who are symbols of holiness and religious power, those associated with the Temple, avoid him, crossing to the other side of the road so as not to have to be near him (10.31-32). But then a Samaritan comes along. The Samaritans were marginal members of Jewish society, because they did not participate in the Temple cult, and did not view Jerusalem as holy. But this outcast is the one who demonstrates the compassion of God. He rescues the stranger and pays for his treatment (10.33-36). Once again we find Luke stressing the way in which it is actually the powerless which prefigure the Kingdom of God.

Edward Blair Leighton, "The King and the Beggar Maid" (1898)

Conclusion

Indeed, the wealthy and powerful were by Luke's estimation, both objectively disordered and subjectively deaf to the message of repentance and had no interest in a real coming of the Kingdom of God. The rich man had been given ample opportunity, Luke warns, even miracles would not change the mind of him or those like him (16.27-31). This is why Jesus was sent to the dregs of society, to those who could hear a message of hope. As the religious leaders of the day complained, Jesus ate with prostitutes and tax collectors, stayed in their homes, treated them as neighbors. For Luke it is not the poor who are thieves, but those who profit off of others in supposedly legitimate ways and go home with a clean conscience at night. This is why Luke threatens society with the great reversal. The last will be first, and in the end the first will be last, because it is those who are society's last, those who are not enmeshed in this world, who are closest to God.

-LoA

2 comments:

hey what is that picture saying ?

i think you are asking about the last one ("the king and the beggar maid"). the story of cophetua and the beggar maid was very popular in the victorian period, because tenneyson wrote a poem on the topic. it is often taken as a man falling in love with someone who is socially inferior. but i think in leighton's painting the king realizes that she is his superior: royalty bows to lady poverty.

Post a Comment