Jean-Leon Gerome, "The Dance of the Almeh" (1863)

First Delacroix and then his protege, Jean-Leon Gerome, had set the standard for orientalism in the first two thirds of the nineteenth century. What had begun as curious perusals of Arabians and Indians (both Asian and American) in Delacroix, had been elevated to the level of masterpiece size interpretations of Arabia. It was thus no surprise that as the French and English political bodies delved more deeply into this unknown world, painters, fascinated by the stories and colors of the orient turned to Gerome, not only for instruction and guidance but, as the rule by which to judge their own achievements.

And Gerome was indeed a challenge to live up to. Arabia opened up to him and he rendered that Arabia from vantages that had never been seen before: portraying private worship (especially a number of Cairo scenes) both in and outside mosques, the interior of royal courts, and topping Delacroix's lonely odalisques, Gerome was granted entry into the sanctuary of the harem and the baths. These scenes were alive with color and charged with barely contained energy and sexuality. Gerome's Arabia was an exotic and erotic playground for the European imagination. Even as Rousseau had argued for the beauty of a more natural world a generation before, Gerome was portraying the European vision of what nature would look like, absent the civilizing impulse.

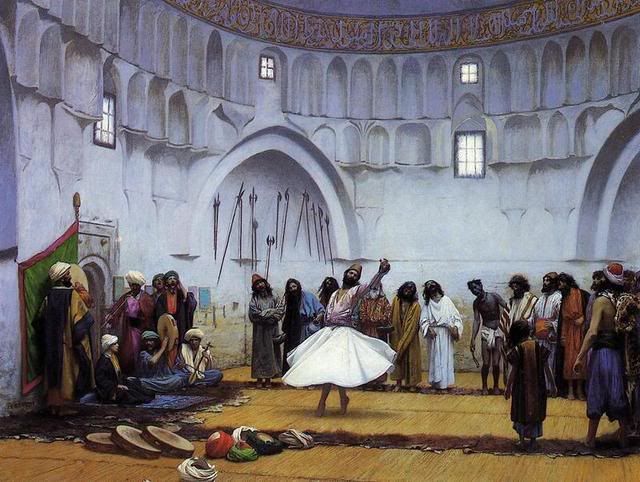

Jean-Leon Gerome, "Whirling Dervishes" (1895)

This visual claim to have laid the Arabian world bare was a key element of Gerome's success. But it was largely a lie. As i have argued before, Gerome does not really grasp Arabia as a whole, but instead divides it into easily consumeable bits, isolated realities that lack a historical or social context. This trend would be followed by the next generation in painters such as Mowbray who unabashedly lays out the orient as a fantasy world lacking depth.

Henry Siddon Mowbray, "Oriental Fantasy" (1887)

The Bostonian, Edwin Weeks, was also among those who sought to learn about the orient and its portrayal from Gerome, but a painter can only learn so much sitting in the studio. So after a time with Gerome and Gerome's close friend L

Edwin Lord Weeks, "The Gate of Shehal, Morocco" (1880)

There is something about Weeks' body of work which reveals that he understood he could not lay bare this world to which he was so totally a foreigner. It begins with the modesty with which he described his work. He was a colorist, not an orientalist. He was not someone who could expose the orient to the viewer no matter how long he travelled there (and he did spend a good deal of the remaining twenty years of his life traveling through P

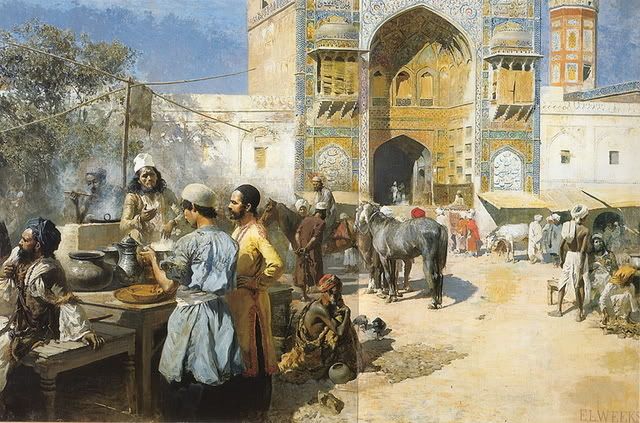

Edwin Lord Weeks, "Open-Air Restaurant, Lahore" (1889)

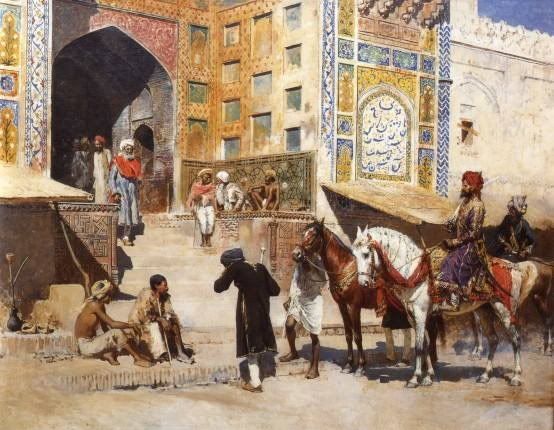

On the one hand, Weeks generally approached his oriental subjects from the exterior. Weeks has market scenes reminiscent of Gerome's time in Cairo, but also palaces that are viewed from their courtyards, or from outside their walls, and heads of state, but only as they travel through the city. This self-enforced vantage point can be seen in two of Weeks' paintings of the mosque at L

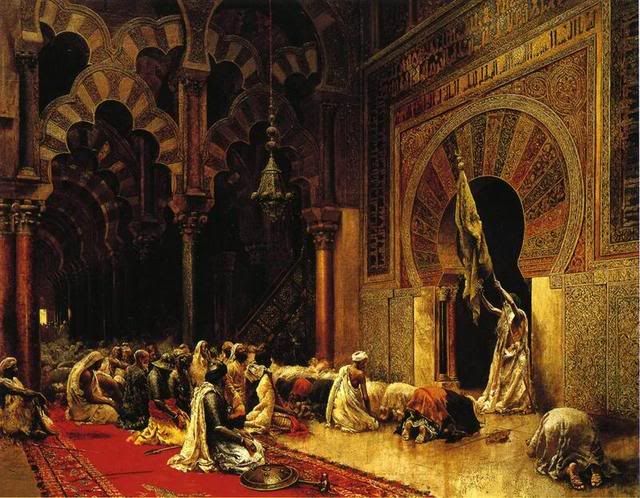

Edwin Lord Weeks, "The Interior of the Mosque at Cordova" (1889)

The exceptions to this general practice by Weeks only confirm this idea. Weeks' great mosque interior, which shows men at prayer, is "The Interior of the Mosque at Cordova". Here a few things must be pointed out. First, Weeks chooses to render the interior of a mosque that is on European soil. And while the painting is historical in its content, the title is minimalist. Weeks uses the title to call attention only the mosque interior, reminding the viewer of the history of the building now known in another form. His historical renderings of the Moorish period in S

This brings us to the final point concerning Weeks' modesty. Unlike Gerome's work, Weeks' is striking in the lack of harems, baths, prostitutes, courtesans, and even the interior of royal courts with the fanciful animals that Gerome portrayed. This cannot be attributed to lack of access. As Weeks notes, the Muslim world was so open and friendly to his arrival in northern colonial I

-LoA

Edwin Lord Weeks, "Riders in front of the Mosque at Lahore" (1889)

Saturday, December 16, 2006

standing outside the mosque in lahore: the modesty of edwin lord weeks

Labels:

art,

edwin weeks,

islam,

jean-léon gerôme,

middle east

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

9 comments:

Fascinating :) Thank you once again fro introducing me, at least, to an artist I was not familiar with, and describing him and his works so well. Weeks seems to have had the modesty of truth, which does not say, or paint, more than it knows.

Peace and Blessings!

Wow. This was an absolutely amazing read, seamlessly guiding me through a subject I know little about.

thank you both. weeks is quite an interesting case, and i had some fun writing this one up. it was my pleasure to play a bit of the tour guide to you both.

Dear LoA,

I have fallen in love with your blog! I came here from Amygdala's and I loved this post so much I can't bring myself to shut the window! Inshallah, I'll sit again and read through all your posts. I love art and culture and your post has been very informative.

Thank you so much.

thank you for your very warm response to this post and the blog. i think your inability to shut the page may have more to do with the beauty of the images than with the quality of my writing. i know they mesmerize me. i hope you continue to enjoy your visits here and i look forward to seeing you around.

p.s. thanks for the link and kind words on your own page.

LoA.

the images are stunning, and the writing is absorbing mashaallah. I would love to read more about this. Orientalism is a strong interest of mine but I know very little.

thank you very much. i admit that my own knowledge of orientalism is quite limited as well. this is how i feel most comfortable approaching the topic: through the art of the victorian era with its traditions of portrayal, technique and methods. of course the painters only have access to orientalist topics because of the imperial expansion of england and france (et al.) and so are themselves its participants and historians just as much as the writers that are the focus of said's work.

which is all a convoluted way of saying, 'ya write what ya know'. :)

glad you enjoyed...

"which is all a convoluted way of saying, 'ya write what ya know'."

Nerdy and trying to be ditzy, eh?

OK, I'll stop.

bis-b-Allah sedeeki, good post, thank you for being so informative

Post a Comment